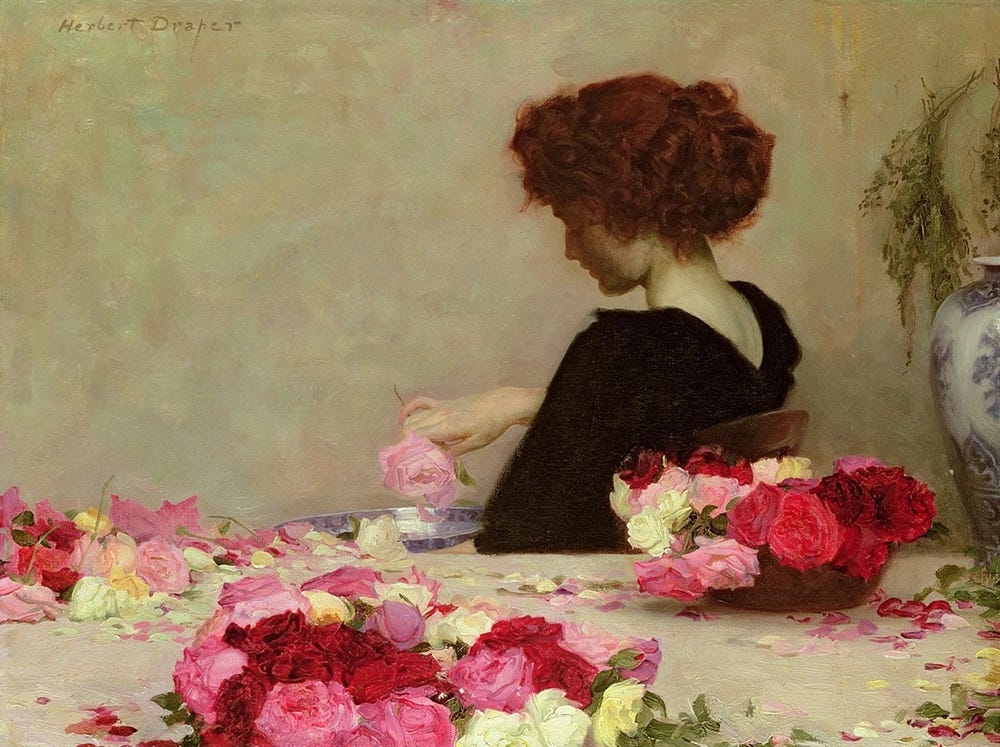

The nose supreme

Smell was our first sense, and it was so successful that in time the small lump of olfactory tissue atop the nerve cord grew into a brain. Our cerebral hemispheres were originally buds from our olfactory stalks. We think because we smelled.

Diane Ackerman, A Natural History of the Senses

Nothing pulls you through a time portal faster than a familiar smell. Visual impressions take a moment to process, as do audio cues, but the reaction to a quick sniff is often violently Pavlovian, feelings leaking out before you know why. Current work in neuroscience shows that smell has a direct, “fast lane” connection to the brain’s emotions and memories systems.

When we get a whiff something familiar, the information isn’t initially routed through the thalamus, like audio or visual inputs. Odor signals travel from the nose to the olfactory bulb and then into the amygdala and hippocampus, bypassing this sorting center where things seen, touched and heard first go. The amygdala and hippocampus modulate emotional responses and memory retrieval. When a familiar smell is linked to a highly emotional moment, it activates a network of brain regions, and you are miraculously transported back in time.

Smell reigns supreme as a subversive force, bypassing reason to expose naked truths that literature exploits, societies suppress, and modernity commodifies. Studies comparing memories triggered by other senses have shown that odor-triggered memories are more emotionally intense and go farther back in time. They appear to be less rationalized, rawer in perception, and last longer.

It is a knee jerk reaction sight alone cannot provide. This is sometimes called a “Proustian moment” - a sudden, vivid rush of memory triggered involuntarily by a sensory cue, especially a smell or taste. It’s named after French writer Marcel Proust, who described tasting and smelling a madeleine biscuit dipped in tea, and being overwhelmed with joy and detailed childhood memories in the first volume of his novel In Search of Lost Time.

No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin.

…

And suddenly the memory returns. The taste was that of the little crumb of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before church-time), when I went to say good day to her in her bedroom, my aunt Leonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of real or of lime-flower tea. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the interval, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks’ windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the forms of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness.

…

And once I had recognized the taste of the crumb of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-flowers which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like the scenery of a theatre to attach itself to the little pavilion, opening on to the garden, which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated panel which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I was sent before luncheon, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine. And just as the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little crumbs of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch themselves and bend, take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, permanent and recognisable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, 1913

Researchers have proposed the LOVER model for how odors cue memories: Limbic, Old, Vivid, Emotional, and Rare.

Limbic: Strong engagement of limbic areas like amygdala and hippocampus.

Old: They tend to reach further back into childhood than memories evoked by other senses, especially in older adults.

Vivid: People rate smell‑triggered memories as clearer and more detailed than image‑triggered ones.

Emotional: They are often strongly positive or negative, and can be tied to joy, nostalgia, or trauma (e.g., in PTSD).

Rare: These “Proustian” moments don’t happen constantly, which may make them feel especially striking when they do.

Studies have shown that odors are more effective than audio cues for autobiographical recall in Alzheimer’s, fishing out what’s long lost in the murk when other prompts can’t.

Scent has long been a part of storytelling. Perhaps the biggest virtuoso in this regard was the scandalous 19th century literary personality Colette, who was also a connoisseur of perfumes and fragrances. She speaks of scent with familiarity and precision, describing it as real and pulsating, rather than a frozen snapshot. For example:

Breathe in the pine and mint from the little salt marsh; its fragrance is scratching at the gate like a cat!

Colette, Break of Day, 1928

I kissed the gleaming smooth hair which had never been curled or waved, the plainly dressed hair which smelled only like the fur of some clean animal.

Colette, The Retreat from Love, 1907

The most famous novel revolving around smell is Patrick Süskind’s Perfume: Story of a Murderer, a disturbing tale of a serial killer obsessed with the scent of virgins. The whole book is a nightmarish olfactory hallucination. Here’s a description of the aroma the protagonist murders for:

This scent had a freshness, but not the freshness of limes or pomegranates, nor the freshness of myrrh or cinnamon bark or curly mint or birch or camphor or pine needles, nor that of a May rain or a frosty wind or of well water…and at the same time it had warmth, but not as bergamot, cypress or musk has, or jasmine or narcissi, not as rosewood has or iris…This scent was a blend of both, of evanescence and substance, not a blend, but a unity, although slight and frail as well, and yet solid and sustaining, like a piece of thin, shimmering silk…and yet again not like silk, but like pastry soaked in honey-sweet milk – and try as he would he couldn’t fit those two together : milk and silk! This scent was inconceivable, indescribable, could not be categorized in any way – it really ought not to exist at all.

Patrick Süskind, Perfume: Story of a Murderer, 1985

Gabriel García Márquez shoots his scent descriptions like a literary cupid:

It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love.

Gabriel García Márquez, first line of Love in the Time of Cholera, 1985

Or:

She returned many years later. So much time had passed that the smell of musk in the room had blended in with the smell of the dust, with the dry and tiny breath of the insects. I was alone in the house, sitting in the corner, waiting. And I had learned to make out the sound of rotting wood, the flutter of the air becoming old in the closed bedrooms. That was when she came.

Gabriel García Márquez, Someone Has Been Disarranging These Roses, 1952

Among Russian writers, Anton Chekhov had an olfactory streak, often painting a striking picture with a couple of strategically placed smells:

The rustle of her skirts, crackle of her corset and jingle of her bangle, and that vulgar smell of lipstick, aromatic vinegar and perfume stolen from the master aroused in me, whilst I was cleaning the rooms with her in the morning, a sensation as though I was taking part in something obscene with her.

Anton Chekhov, A Story of an Unknown Man, 1893

I see a cloud there resembling a grand piano. I make a mental note that I must remember to mention somewhere in my story that a cloud resembling a grand piano floated by. Smells like heliotrope. Note to self: a sickening sweet smell, a widow’s color, must mention when describing a summer evening.

Anton Chekhov, Seagull, 1896

In Fat and Thin (1883), Chekhov uses smells for social contrast:

Two friends met at the Nikolaevsky train station: one fat, the other thin. The fat man had just dined at the station and his greasy lips shone like ripe cherries. He smelt of sherry and fleur d’orange. The thin man had just stepped off the train and was laden with portmanteaus, bundles, and bandboxes. He smelt of ham and coffee grounds. A thin woman with a long chin peaked out from behind his back — his wife, and a tall schoolboy with one eye screwed up — his son.

Nabokov pins you to a specific feeling, like an entomologist securing butterfly:

She wore a nunnish brown dress and gave off a slight but unforgettable smell of coffee and decay.

Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory, 1951

And

I recall the scent of some kind of toilet powder - I believe she stole it from her mother’s Spanish maid - a sweetish, lowly, musky perfume. It mingled with her own biscuity odor, and my senses were suddenly filled to the brim …

Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita, 1955

Dostoyevsky’s descriptions of smell strike me as overwhelmingly negative, conveying disgust. He doesn’t dwell on the odors and the descriptions read as moral judgements rather than sensory experiences. His St. Petersburg consistently feels like olfactory claustrophobia and reeks of stagnation.

The heat in the street was terrible, and besides that the airlessness, the hustle and bustle, lime plaster everywhere, along with the scaffolding, bricks, dust and that particular summer stench, so familiar to any St. Petersburger unable to rent a summer house — all impressed painfully upon the young man’s already frayed nerves. The insufferable stench from the taprooms, which are particularly numerous in this part of the town, and the drunks whom he encountered constantly, despite weekday working hours, completed the revolting misery of the picture.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment, 1866

George Orwell echoes some of this with his class distinctions through smell:

But there was another and more serious difficulty. Here you come to

the real secret of class distinctions in the West — the real reason why a

European of bourgeois upbringing, even when he calls himself a Communist,

cannot without a hard effort think of a working man as his equal. It is

summed up in four frightful words which people nowadays are chary of

uttering, but which were bandied about quite freely in my childhood. The

words were: The lower classes smell.George Orwell, The Road to Wiegan Pier, 1933

In his other works, scent surfaces as a symbol of class again:

Simultaneously with the woman in the basement kitchen he thought of Katharine, his wife. Winston was married—had been married, at any rate: probably he still was married, so far as he knew his wife was not dead. He seemed to breathe again the warm stuffy odour of the basement kitchen, an odour compounded of bugs and dirty clothes and villainous cheap scent, but nevertheless alluring, because no woman of the Party ever used scent, or could be imagined as doing so. Only the proles used scent. In his mind the smell of it was inextricably mixed up with fornication.

George Orwell, 1984, published in 1949

Smells as a social verdict make me think of the Moscow metro in the 1990s. The long outgrowth of metro lines extending to poor neighborhoods on the periphery, with their bleak, copy-pasted high rises and dense sense of doom. There was a very distinct smell in the subway cars in the winter. Damp old leather coats and wet fur, heated stale air, collective breath tinged with sickening lunch meats and onion.

As time went by and the oil boom awarded residents some dignity, gradually raising quality of life, the smell aired out of the city’s underground. New subway cars, pleasant perfumes, better-dressed people and modern ventilation systems took over the familiar, warm dustiness of the metro. But to me, the signature scent of poverty from the nineties remains unforgettable - the ominous fug of despair.

Cities themselves are ripe with unique scents. Moscow is a spring sun flirting with the dewy, dreamy scent of lilacs in May. By sundown, you are drunk on the lilacs, the nightingale songs giving you goosebumps of anticipation of the warm nights ahead. Or the cocktail of autumn - the tender drizzle, wisps of car fumes, traffic lights reflected in the puddles, wafts of coffee and various hot foods competing with each other in the street, women floating by in clouds of tart perfume, and underneath it all the rich, fertile breath of wet earth.

New York to me was oppressive in the summer, decaying garbage awaiting its turn in the streets, and air too thick for comfort. The one smell I associate with New York is the exhale of laundry into the street, a generic, warm rush of synthetically scented detergent. It felt like everything smelt of this exhaust – the streets I walked down, the parents I hugged in greeting, the people I passed in the streets. As if all of them were laundered in a communal city centrifuge, scented accordingly.

I underwent a stark nasal awakening in my twenties. I’d started smoking very young and smoked for many years. When I quit abruptly, something drastic happened. I acquired almost canine capabilities in what I was able to sniff out. I couldn’t use perfume anymore because it became too overwhelming, I was too aware of it, it weighed on me physically, the layers of fragrance too heavy to carry all day. I was bombarded by smells in every room I stepped into, smells I could tangle apart and catalogue, smells that were often distracting. It took some getting used to.

When I had covid a couple of years ago, I lost my sense of smell for a week. Few things have made me panic this much. The family poked fun at me as I started every morning sniffing the most odorous things in the fridge – the little can of horseradish, the kimchi, the cheeses. I was desperate to train myself back into sensibility. Smelling my own fingertips and sensing nothing drove me crazy. I cut off sprigs of my lavender and stuck them up my nose to loud hoots from the husband and child, desperate to coax out my sense of smell. Thankfully, it all came flooding back.

Most of what we call flavor comes from our sense of smell. The tongue detects only five basic tastes - sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. It’s smell that integrates thousands of aromas to create complex pleasure. When your sense of smell is impaired, like with covid, distinguishing the taste of foods is a struggle.

Beyond flavor, smell governs human connection. Women relying more on odor than visual cues for mate selection makes complete sense to me. I think compatibility and acceptance is reflected in always liking how the other person smells. When he’s fresh out of the shower or sweaty, sleepy or sunburnt, there is an instantly recognizable undercurrent that triggers a positive response. You need to soldier past the deodorized veil of modernity to drink in a lover’s real aroma. Then, the nose knows just as well as the heart does.

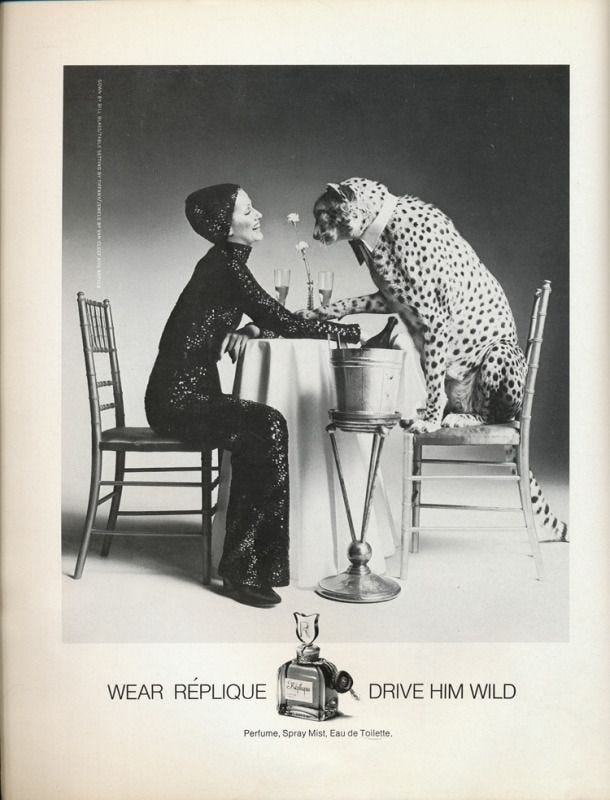

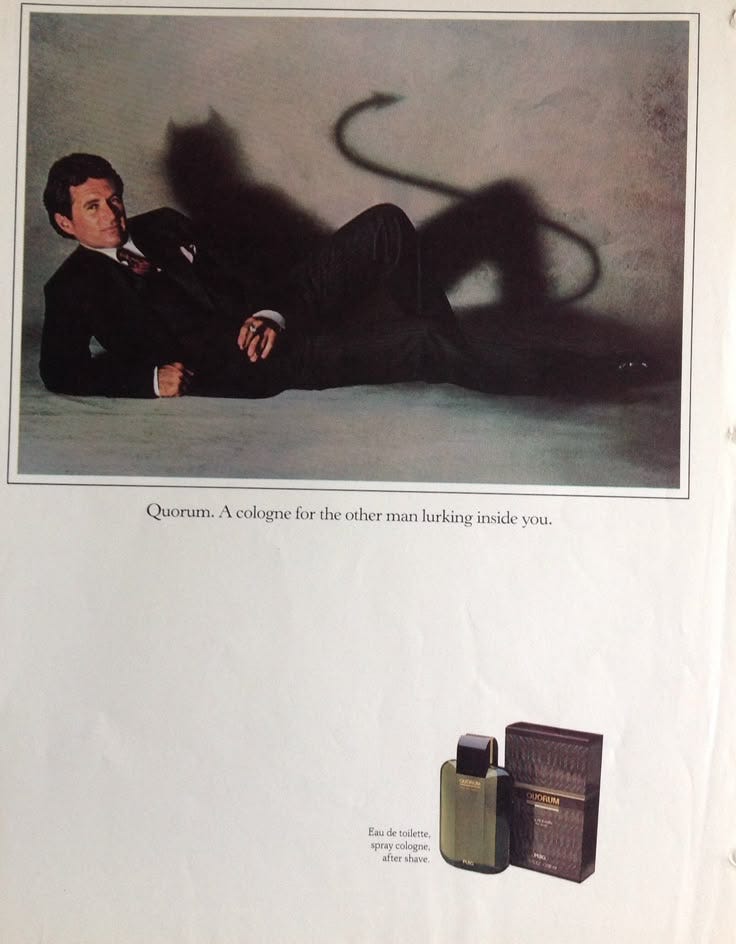

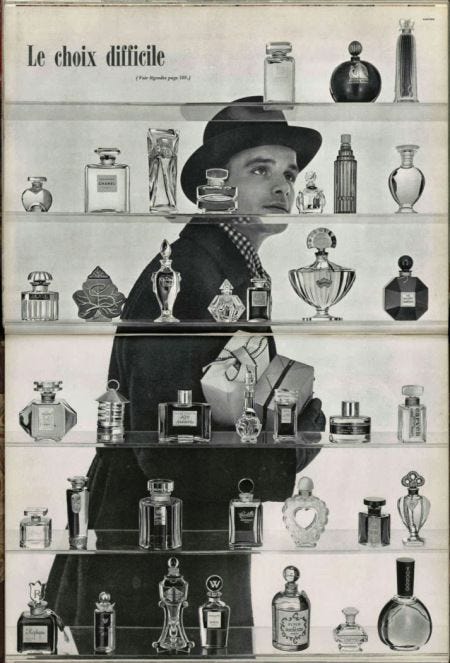

Aldous Huxley understood the power of smell as a psychological trigger and logically made it one of the key tools of infantilization through sensory overload. In his Brave New World (1932), “scent organs” are mechanical devices that disperse synthetic aromas during feelies (immersive films), replacing real human experience with programmed pleasure. This was Huxley’s satire of a hedonistic society where natural sensations are commodified and controlled. Reads a tad prophetic today, with our scented candles and air fresheners, strategically smelling retail spaces, and realtors with their freshly baked pastries as a standard home staging trick.

Yet smell’s primal wisdom remains irreplicable. It’s the most evocative of our senses and an intrinsic part of the human experience. A city will reveal itself as magnolias and bird-cherries battle with stinky alleys and muddy rivers for scent supremacy. When my pristine canine princess is exposed to the elements and suddenly smells abashedly like wet dog, I get a giddy thrill. Masking this with the scent of a supermarket shampoo aisle seems criminal. No diffuser can outdo the cozily stale smell of a home long left alone.

People’s scents feel intimate and sacred. The smell of them when all other smells have been peeled away, known only to the closest few.

My grandmother died when I was thirteen, decades ago. I try to conjure her fragrance but can’t, only a feeling of it remains – the faint woolen smell of her cardigan and a sense of her lean frame in motion, a cool airiness to her, an unscented, natural freshness. It’s an encore of loss, forgetting the smell of those you loved most.

When my sense of smell vanished during illness and then returned, I realized that breathing in the world is knowing it, being a part of the greater continuum. Scents are invisible fingerprints of life itself, proof that something exists, responds, renews.

Literature’s greatest maestros, from Chekhov to García Márquez, illustrate that a life without smells would be a life of amnesia, a dystopia where all other senses are castrated in the resulting domino effect. Long live the free-range nose - the great enhancer, our window into the past and existential anchor to the present.

This nails something profound about memory's power over us. That fast lane bypass, where smell skips the thalamus and hits emotion directly, explains why certain scents ambush us. Last year hospital antiseptic triggered a grief response beacuse of a family thing, and it's wild how defenseless you are. The unfiltered quality of smell-memories doesn't give you time to prepar yourself.

Now I must sniff out these books (some I know already, e.g., Dostoevsky of course).