I find the romanticization of socialism, with its Marxist origins and aspirations, very off-putting, at best a childish fantasy from a picture book of everyone frolicking in fields of equity with rainbows of opportunity coming out of their backside, and in reality, maliciously idiotic and blind to the painful history of several countries and generations.

For me, the whole thing isn’t a highbrow idea to throw around at dinner parties, the appropriate seasonal decoration to hang for approval and acceptance, an exhibitionist display to flash in everyone’s face as a sign of your moral superiority. It’s personal, a lived family saga.

Here’s a pedestrian rundown of one branch of my family tree, by no means unique where I’m from, and in essence a socialism-lite story.

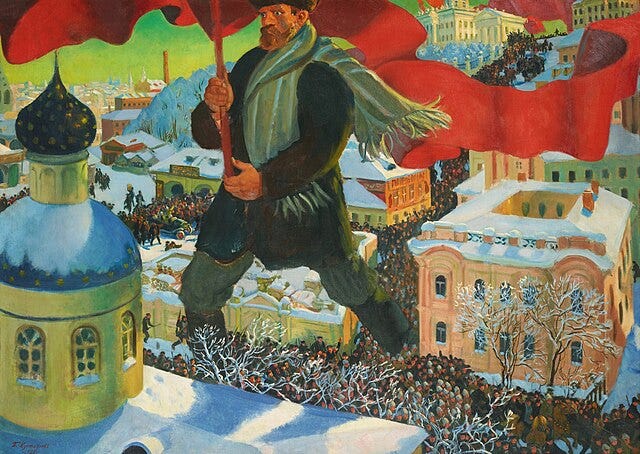

My maternal great-grandmother was born at the turn of the century to a long line of Moscow merchants and small business owners. They were part of the middle class of the time, consisting of professionals, civil servants and other educated city dwellers. Through a remote noble relative, she had access to a subscription box at the Bolshoi, where she attended all the operas as a teenage girl and much later delighted my tiny mother by knowing them all by heart. There were also the less delightful but typical stories of hordes ransacking the family home, ripping out wooden flooring and gold spines off the Bibles as she watched. These were no lavish estates dripping velvet and jewels, but regular city homes of people who had worked for generations to build them and everything they had. Her father’s capitalist exploitation manifested in owning and running a shop in the “Upper Trading Rows” in Red Square. The Red Terror that started during the revolution saw about half a million people slaughtered by their fellow countrymen for unacceptably owning things, including peasants who owned farmland, as well as working a government job, engaging in “bourgeois” pastimes and other such crimes against the righteous mob.

Here’s a fun 1918 telegram from Lenin on “Hanging 101”. This is not a dystopian Netflix series, but the Soviet day to day.

"Comrades! The insurrection of five kulak districts should be ruthlessly suppressed. The interests of the whole revolution require this because 'the last decisive battle' with the kulaks is now underway everywhere. An example must be made.

Hang (absolutely hang, in full view of the people) no fewer than one hundred known kulaks, fatcats, bloodsuckers.

Publish their names.

Seize all grain from them.

Designate hostages - in accordance with yesterday's telegram.

Do it in such a fashion, that for hundreds of verst around the people see, tremble, know, shout: "the bloodsucking kulaks are being strangled and will be strangled".

Telegraph the receipt and implementation. Yours, Lenin.

P.S. Find tougher people."

My great-grandmother met my great-grandfather as he was graduating Vkhutemas, an awkward mouthful of a Soviet acronym for what were previously two of Russia’s top schools of design and fine and applied arts. It was an incredible ground zero for the Russian avant-garde, with courses taught by the likes of Rodchenko, Popova, Udaltsova and later Kandinsky and Malevich. The Architecture Department where he studied was led by Melnikov, Shchuschev and Sсhechtel, the most prominent Russian architects of the time who among them built plenty Moscow landmarks, including numerous estates and churches, palatial metro stations, constructivist masterpieces, a few railway stations and the Lenin Mausoleum in Red Square.

A couple of years ago, I went on a defiant genealogy bender, determined to extract everything I could from the archives while they were still open to the public. My little guy way of lashing out at the callous Motherland for once again deciding to derail a generation’s lives – you might have left me wandering the globe, holding my bare roots like a skirt, not knowing where to plant them, but I’ll take as much as I can of them with me.

The authorities grew increasingly displeased with this audacious idea fest and by 1930 Vkhutemas was shut down, its departments methodically dispersed and cleansed to prevent any arty nonsense from springing up again in the uniform landscape of the new Soviet world. For the next couple of decades, fearing for their lives, many graduates destroyed their works and tried to distance themselves as much as possible from this unique cauldron of genius and creativity. My great-grandfather struggled for years to find work and feed his wife and children, drawing bar graphs of linen production and teaching where he was allowed. I grew up looking at his mixed media portrait of my great-grandmother on the wall, beautiful but with an air of sadness. His sixty-page case file reads like something out of Bulgakov, report upon report penned by co-workers about his insufficient mingling with the proletariat and bourgeois ways, written in newspeak and slogans. His replies seem to be in a different language entirely, from another time. The reason he wasn’t shot was that one of his sisters married an OGPU (later NKVD) secret police officer, which kept coming up as my ancestor’s only saving grace in his forms. My great-grandfather died in the first months of WW2.

Two quotes to sum up the socialist newspeak and consider modern parallels:

“The socialists have engineered a semantic revolution in converting the meaning of terms into their opposite” - Ludwig von Mises, Austrian-American economist, 1958

“One of my teachers at Columbia was Joseph Brodsky, who’s a Russian poet, wonderful, amazing poet, who was exiled from the Soviet Union for being a poet. And he said look, you Americans, you are so naïve. You think evil is going to come into your houses wearing big black boots. It doesn’t come like that. Look at the language. It begins in the language.” - American poet Marie Howe, 2013

My grandmother dreamed of being an architect like her father but the summer she was turning eighteen, WWII came to Russia. She signed up for nursing courses and six months later was swiftly deployed to the front. She spent four years dragging wounded soldiers off the battlefield on her bony shoulders and educating medical personnel. As a kid I remember running my hands down a landmine scar, a rugged constellation of craters, that stretched from the inside of her elbow to her delicate wrist. She was a tall, regal looking woman, who would pop out for a smoke onto the landing while I was told to watch the hockey score, CSKA for the win. Later, family members recounted details of her escaping Vlasov army captivity, miraculously surviving wounds crawling with maggots, while slipping in and out of consciousness for days on a slow rolling medical train, pouring vodka in the festering gash.

After the war, she worked as a drafter and went through a variety of harsh factory jobs. In 1954 she met my grandfather, who had just been released after a seventeen-year-old stint in the Gulag in a “rehabilitation” of political prisoners following Stalin’s death in 1953 (so already almost 40 years of the country living in terror). The grandfather’s crime was being a Polish aristocrat during the 1937 purges, specifically in the Polish Operation episode. During his years in the camps, his first wife had perished in the hell of WW2. Although he was much older, he was a looker and a gentleman, and sparks flew.

The social climate was such that people were terrified of being associated with repressed persons, up to the point of crossing the street when they were walking by. Memories of black cars showing up to take random neighbors away into the night were too fresh. Historians estimate that in 1930-1953, 18 million people passed through the Gulag - forced labor camps, others say this number could be closer to 25 million. This is not including those who were shot or tortured to death and not sent anywhere.

My grandfather had been a pilot captain, they restored his army titles and then some, gave him an allowance, but society wouldn’t give people like him their dignity back. They were still considered pariahs to be steered cleared of. My great-grandmother was adamant that my grandmother have nothing to do with him, that it was a death sentence, poems and letters were burnt. Given her experience of the revolution and its aftermath, her fears are understandable. Then my grandmother got pregnant. Forever cursing a child to be born of an “enemy of the people” was beyond scandal and my great-grandmother’s siren went off at full volume. My grandmother broke it off, and the year my mother was born my grandfather suffered a debilitating heart attack that he never recovered from, dying several years later. He was only fifty something. My mother never knew him but looks exactly like him, as we learned from pictures uncovered decades later and the Polish matches in her 23andme results.

It’s not all a sob story of pitchforked dreams and pillaged futures. The family tree has instances of poor peasant’s sons shooting up to the top as diplomats and other shiny members of the new elite, but those are rare. Incidentally, descendants of said individuals are the biggest fans of everything Soviet. I always point out that this Animal Farm story of having a designated fireplace person, cleaner, driver and cook is not representative of the general population’s experience but get dismissed as a ruinous Russophobe corrupted by my Western education.

Over on my husband’s side of the family there are centuries of modest small-town gentry, abruptly ending with the usual rampage and looting, leaving a handful of forbears to live on in dire poverty, but live nonetheless, very generous for the times. A great illustration of the humanitarian nature of these great socialists is how they officially referred to both our ancestors as “former people”.

The 1939 NKVD Order No. 001223, which established the detailed bureaucratic procedures for keeping track of "anti-Soviet and socially alien elements", defined the category of "former people" as follows: "former tsarist and White Army administration, former dvoryans [Russian nobility], pomeshchiks (noble landowners), merchants and petty merchants, those who employ hired labor, industrialists, and others".

There were up to 35 million “former people” out of a population of 170 million people, so about 21% of the population or 1 out 5 people was labelled inhuman and treated as such.

These great liberators were also inventive in their well-documented slaughter of “former people” during the revolution and throughout the ensuing terror. We know this from countless memoirs of the time. In his diaries Soviet literary critic Viktor Shklovsky gushes about the 1917 revolution:

“I was a happy part of these crowds. It was Easter and the merry, naïve paradise of Butter Week! Shops, police stations and trams were smashed. A special treat was having fun with the raspberries (junior rank city policemen), killing them by sinking them under the ice of the Neva river.

The revelers, almost playful, didn’t just burn down shops, ‘profiteer’ warehouses, courthouses and police stations. Right in the streets, ‘in the name of freedom’, they ritually burned the ‘enemies of the people’, identified on the spot by the crowd – they tied them to metal beds, which were placed on a bonfire! This could be viewed a subconscious channeling of pagan archetypes, rich in rituals of ‘flogging’ undesirable idols, for instance, burning them during Butter Week like an effigy of the bygone winter. This image of burning the ‘symbols of the old-world order’ were to them none other than an illustration to the cliché of ‘sacrifice on the altar of the revolution.’”

My husband has Old Believers in his lineage who were the OG Russian Orthodox Christians, dissenters that refused Patriarch Nikon’s reforms in the 17th century. They were a stoic folk who persisted through centuries of persecution and hardships. My husband’s ancestors were prominent in the Moscow Old Believer community, its own world with churches, cemeteries, schools and so forth. His great-grandfather and great-grandmother were lucky to only be sentenced to a year in prison, the official charge on the paperwork being “sympathy for an enemy of the people”, meaning expressing concern as someone from the community was dragged away to be jailed. In and out in a year, incredible luck!

I think a Russian family with no history of anyone being sent to the Gulag or unceremoniously shot would be a rarity. This is a story I’ve heard from nearly every Russian friend I have.

My thoughts on the current Marxist masturbation in American media and society are – don’t, it’s not pretty and won’t end well. Nietzsche succinctly summed it up as “the tyranny of the lowest and stupidest, the superficial, the envious and the more-than-half actors.” We’ve already made that mistake for you, go read any book on repression in the Soviet Union, or a random memoir, be it Nobel prize winner Bunin’s “Cursed Days” or a later period female account of the Great Purges and life in the Gulag, Ginzburg’s “Journey into the Whirlwind”.

“Socialism itself can hope to exist only for brief periods here and there, and then only through the exercise of the extremest terrorism. For this reason it is secretly preparing itself for rule through fear and is driving the word “justice” into the heads of the half-educated masses like a nail so as to rob them of their reason… and to create in them a good conscience for the evil game they are to play.” ― Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits

I utterly agree with you. "No socialism for me" as an old immigrant, running to America from Soviet socialism long ago, but socialism ("another kind)" is my daughter and her husband's wish for this country. I think this political absurdity comes from the professors at their colleges who consider themselves progressivists who carry humanism into education.

It continues to beggar belief that it is 'cool' in some circles to sport a hammer and sickle, or a Che image, or a McLenin's t-shirt. Nobody would use a swastika that way.

I am familiar with the 'find tougher people' citation. Many to this day think of Lenin as a nice intellectual whose clever ideas were warped by bad guys. The man was riven with hatred. He didn't care about the poor. He cared about humiliating unto death those he perceived to have slighted him and his family. It was vengeance on a vast, catastrophic scale.